But it turned out that he was a ‘complicated’ man — at least that’s how the doctors described him.

But it turned out that he was a ‘complicated’ man — at least that’s how the doctors described him.

Her brothers brought him home from the ‘glass house’* to meet their sister. That was thirty years earlier.

He was a thrifty, hard-working, unassuming, church-going man. And even though he chewed tobacco, everyone agreed he was swell.

So they married.

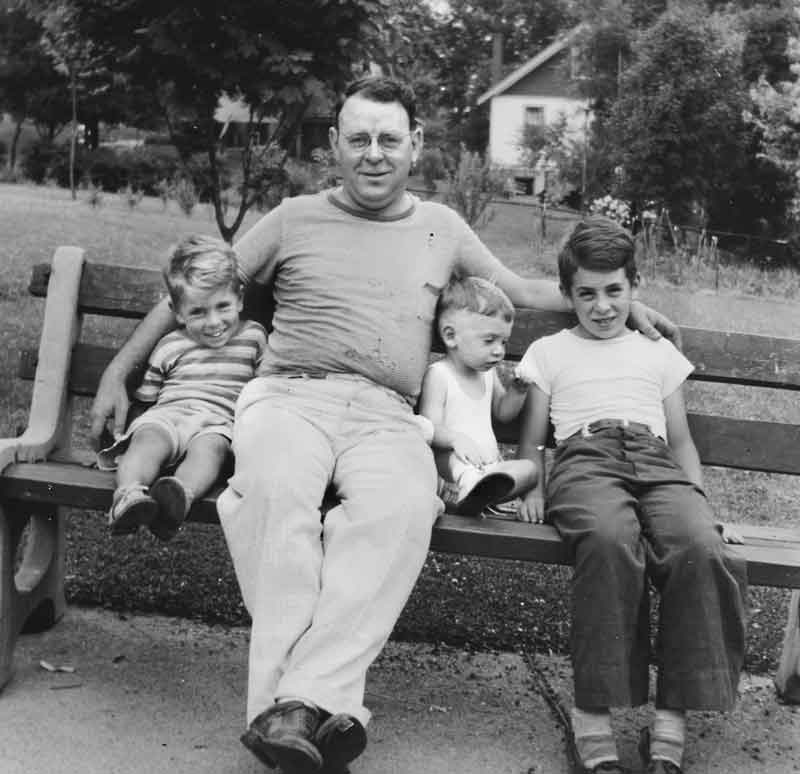

He was good to their boys and except for penny-ante poker, he didn’t gamble. There were no women. But it turned out that he was a ‘complicated’ man.

He had lost his mother and was raised as an only child by aunts who scorned his father and his father’s religion. He could be heard shouting back at them decades after they died. He couldn’t lay them to rest.

As newlyweds, the couple had been familiar with alcohol. The young woman’s father gave dances during Prohibition; her family bragged he could physically pick up and bounce two drunks at the same time. Her husband ran hooch out of an elevator in a downtown hotel.

By the time their second boy came, the man’s diary described how he and his crew carried hip-flasks while sorting mail on train cars. There was a photo of him bleary eyed during a labor event. He frequented distant taverns to hide his growing habit.

Alcohol and undetected diabetes tricked the chemicals in his brain. His outbreaks led doctors to prescribe electric-shock therapy and the courts signed off, twice. There was a fall from grace. Nobody knew what to say.

Don’t stop reading.

It turns out the man was as canny in choosing a spouse as his wife had been in choosing him. She refused to see her good and decent man as a damaged soul. She never wavered. She made sure her boys appreciated that their father, despite his afflictions, gave them full bragging rights. The family held.

The man outlived his wife by about a year. There was beer in the house after she was gone but now it was ice cream he turned to for comfort. He kept Eskimo Pies in the freezer.

* glass production had been a thriving industry in western Appalachia ![]()